Git is a terrifying and powerful instrument. I've been using it for a few years

now and there are still commands that I just won't touch. Up until a few months

ago, one of those commands was git rebase. It's really a shame, since rebasing

is one of Git's most exciting and powerful features. So this article is, in

spirit, a letter to myself a year ago on why I should have been using a

rebase workflow then.

Rebasing from 10,000 feet

In the Git Book, chapter 3.6, the following description is given.

Rebasing replays changes from one line of work onto another in the order they were introduced, whereas merging takes the endpoints and merges them together.

I think this just sounds bizarre. It's absolutely correct, but as a new Git user it made no sense to me at first. I prefer to think of it this way:

Rebasing allows you to take a line of work and pretend you started it somewhere other than where you actually did.

Let's say you have a feature branch feat based on commit A. You create the commits

B and C on feat. In the meantime, someone else commits D and E on

master.

Figure 1: Feature branch and master branch before a rebase.

When you rebase feat onto master, it looks as if you started in feat after the

changes in D and E were applied (assuming no rebase conflicts). You can then

rebase master onto feat, which causes a fast-forward.

Figure 2: Feature branch rebased onto master; master fast-forwarded.

That's it! Nothing scary at all happened. We took the changes from B and C,

pretended we started them on E, and then moved the master branch pointer to

C'. At this point, master is safe to release for public consumption.

Why do I need a rebase workflow?

Almost ever since I started using Git, my good friend and hacking buddy

@nvanderw has tried to get me to use git

rebase. It never worked. He would patiently explain how rebase works and how it

was benefiting him. I would mostly just get annoyed and tell him that my working

subset of Git worked just fine, and rebasing was too complicated and sounded

risky. This went on for a while. I never really got comfortable using git

rebase, and certainly couldn't integrate it into my workflow.

Then I joined a project that uses git rebase exclusively and forbids git

merge.

Suddenly, everything made perfect sense! Before adopting a rebase workflow, my project histories looked like tangled jellyfish - a complicated dag of forks and merges.

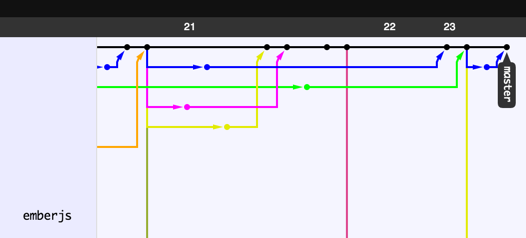

Figure 3: History of a project using a merge workflow.

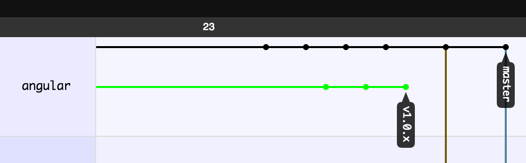

With the new rebase workflow, I always have a neat logical line of changes. At any point in the past, there is always exactly one authoritative version of the project. This makes it significantly easier to find regressions that may have occurred dozens or hundreds of commits back in the history.

Figure 4: History of a project using a rebase workflow. Notice how there are no forks or merges.

The Workflow

Create a feature branch

$ git checkout -b featureMake changes on the feature branch

$ echo "Bam!" >>foo.md $ git add foo.md $ git commit -m 'Added awesome comment'Fetch upstream repository

$ git fetch upstreamRebase changes from feature branch onto upstream/master

$ git rebase upstream/masterRebase local master onto feature branch

$ git checkout master $ git rebase featurePush local master to upstream

$ git push upstream master

Doing it with Style

Since you're doing all of your real work in a feature branch, it's OK to change history in public on that branch. The only way the master branch can change is by fast-forwarding in a rebase. The general rule for rebasing is not to rebase any public code that others might base their work on. No one else should base work on your feature branches, so this workflow is safe.

On a related note, it's a good idea to make a number of incremental commits and

roll them together into a larger logical change before merging them in and

pushing them. git rebase -i is made for this scenario. If I make N-1 commits

in my feature branch, I can use git rebase -i HEAD~N to squash commits

together and reword the commit messages. I can even reorder the commits to make

it appear as if I'm actually doing TDD! (You've been warned: this tactic may not

work if your teammates actually read git timestamps.)

Cherry picking commits can be an effective way of getting code into your master

branch. git cherry-pick is a special case of rebasing which takes a single

commit and applies the changes on top of the current HEAD. I've found it very

useful for applying changes from GitHub pull requests.

TL;DR

Rebasing gives you a clean linear commit history and creates non-obvious benefits to your project if used diligently. Think of it as taking a line of work and pretending it always started at the very latest revision.